I’ve created a collection of commonly held misconceptions and myths about anxiety to help parents comprehend and help their children. I will cover various themes and management strategies related to anxiety at the parent workshop in November. Contact me if you want to be notified via my newsletter.

Myth one: Anxiety isn’t an illness; everyone has it.

Fact: Anxiety is a legitimate, diagnosable disorder

Everyone feels stressed, worried, or anxious from time to time. Because feeling worried or anxious is common and is normal and necessary.

From toddlers to teens, life challenges may be faced with a temporary retreat from the situation, a greater reliance on parents for reassurance. A reluctance to take chances, and a wavering confidence. Generally, these issues are alleviated when the child learns to control the situation or when the situation changes. This may result in reduced anxiety and make a parent consider the possibility of anxiety becoming a mental health issue. In some cases, the worry and apprehension may be so overwhelming that it continues even after the source of the concern is gone. Parents sometimes ignore how this impacts their child’s life in school and in the home.

Anxiety is considered a disorder not based on what a child is worrying about, but rather how that worry affects a child’s functioning. The statistics show it is probably more common than parents think.

According to the World Health Organisation. In 2019, 301 million people lived with an anxiety disorder, including 58 million children and adolescents. Anxiety Disorders are the most common mental health disorder, and are still largely untreated. There are several types of anxiety disorders, such as: generalised anxiety disorder (characterised by excessive worry), panic disorder (characterised by panic attacks), social anxiety disorder (characterised by excessive fear and worry in social situations), separation anxiety disorder (characterised by excessive fear or anxiety about separation from those individuals to whom the person has a deep emotional bond), and others.

Myth Two:Talking about anxiety makes it worse

Fact: Why talking helps

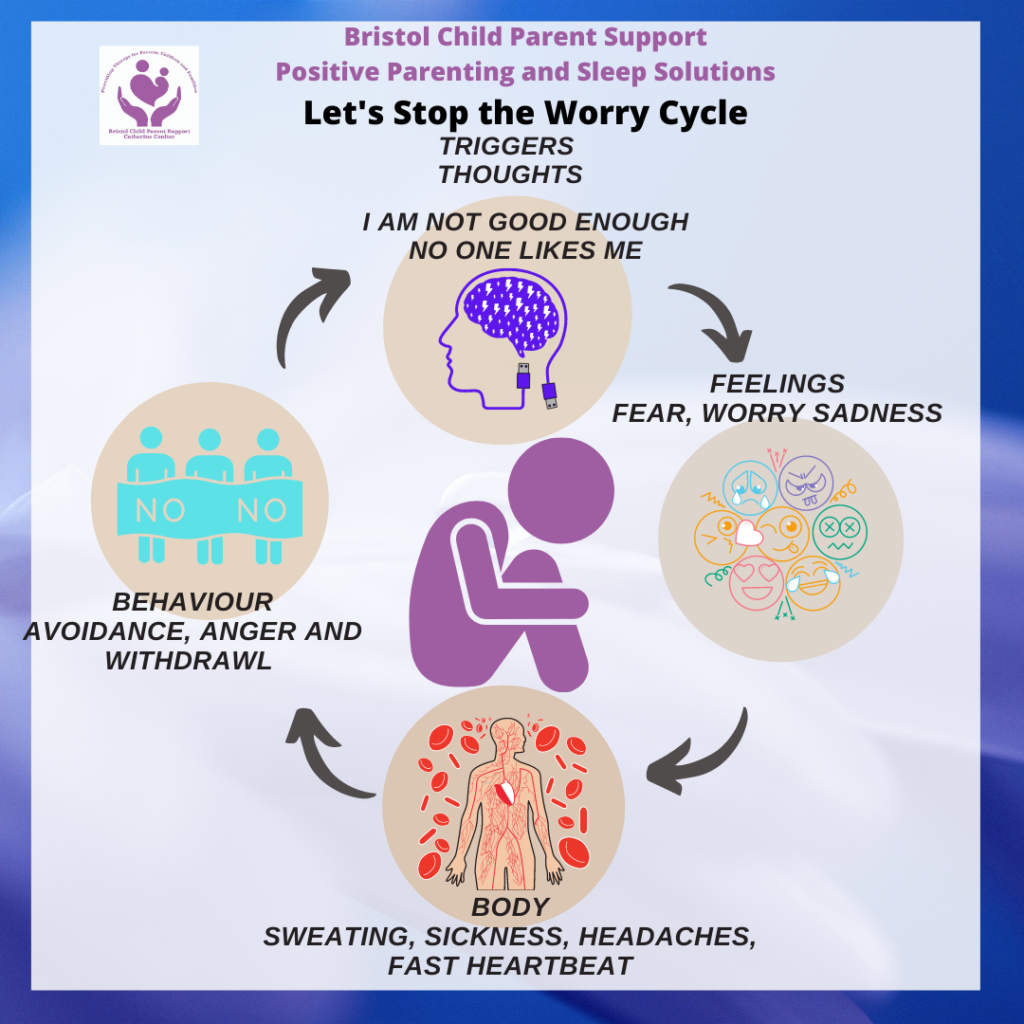

When you’re experiencing intense feelings — especially fear, aggression, or anxiety — your amygdala is in charge.

The amygdala, a component of the limbic system, takes charge when your body senses a threat. This is known as the fight-or-flight response. It processes the danger, formulates an appropriate response, and stores the information in your memory for future encounters. This can cause you to become overwhelmed, and can even override more rational thinking.

Research from UCLA suggests that putting your feelings into words — a process called “affect labelling” — can diminish the response of the amygdala when you encounter things that are upsetting.

Research shows that areas of the brain associated with emotion and language development are not fully developed until late adolescence. Therefore, children may not understand why they’re feeling a certain way or why they act a certain way. They rely more on emotion than on rational thought due to a developing prefrontal cortex. Very young children will only recently have mastered the skills of walking and talking, and they may not be able to express their anxieties and fears. Even if you believe they are too young to comprehend, even small children can internalise scary occurrences from the media or discussions they accidentally hear.

Therefore, it is crucial that you, as the parent, wonder, to put into words (and label) what they might feel, and help them make sense of the link between their behaviour and emotions. Watch your children for signs of fear and sadness they may not put into words.

- Have your children become extra clingy or need more hugs than usual?

- Have your children started old habits after you thought they had outgrown the behaviour? Are they suddenly more irritable?

- Are they complaining of tummy aches and headaches going to school or bedtime?

They maybe feeling the pressure of what is going on in the world around them. By discussing your child’s fears, you allow them to feel understood and not alone in their worries.

Simple ideas on what to say and do

Always empathise with your child and mirror back what they are feeling. For example

“That must be really hard for you”

How can I help?

“I wondered if you might feel worried. Many children at your age feel worried about these sorts of things, and you are not the only one”.

“We are safe, rather than I am keeping you safe”, is better.

It can be challenging for younger children to talk about themselves. One useful approach might be to ask them about their best friend, or what they might be feeling. An alternate option could include talking through puppets, lego, or soft toys to act out different scenarios.

Myth Three: Avoiding situations will help my child manage anxiety.

Fact: Avoiding situations helps no child manage anxiety.

Avoidance of anxiety comes in many ways for children. It may be very subtle and start to creep up gently, without you being aware at first. Your child may start to say things like “I don’t want to go there, they were mean last time”. That was boring at Beavers.” You may observe that your child begins to distance themselves from certain activities or events over time.

Parents may not like seeing their child distressed in a situation that causes them anxiety, and want to protect them from the distress. Though there may be some immediate relief, disregarding these trying times can be detrimental in the long haul, as it prevents them from learning how to be independent (apart from you) and reduces their involvement in social activities.

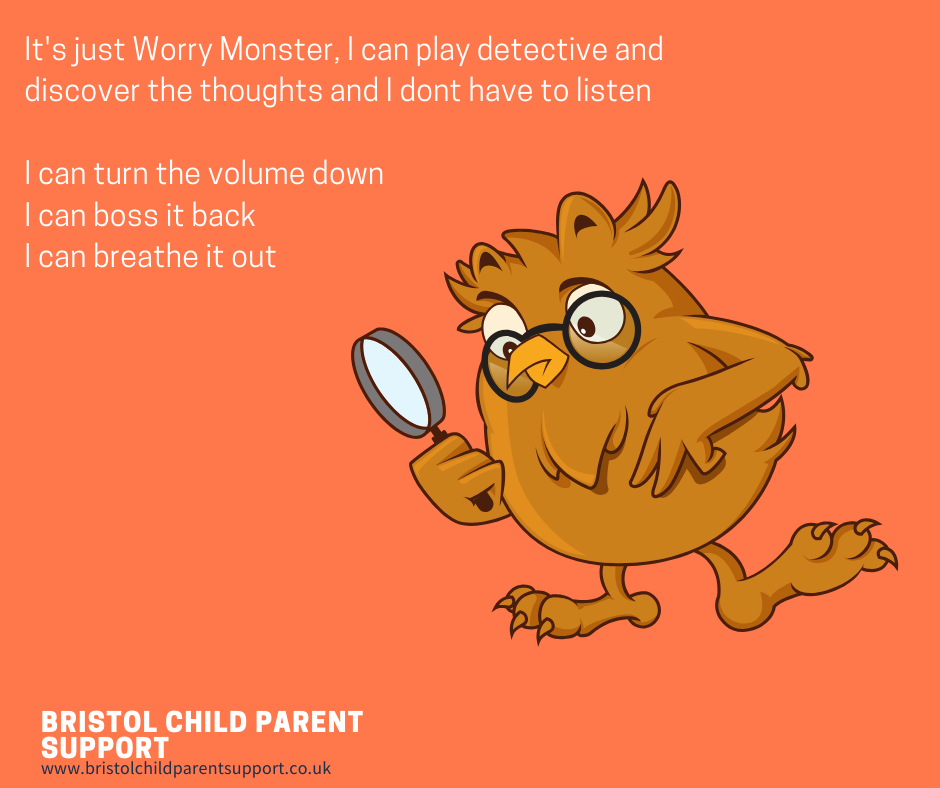

They just want you to keep them safe. Your challenge is to empower your child and, over time, teach them they are brave and safe. They need you to help them identify and talk about their fears, and then help them manage them. By teaming up, you can help them feel less alone and empowered, and act toward their goals. This is often called exposure therapy.

Exposure therapy comes from Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. It means you gradually and systematically introduce your child to the things they’re afraid of or that make them anxious. This helps them manage their fear or anxiety. If your child doesn’t face their fears, they’ll always be scared. You can use the ladder analogy below to rate your child’s fears before getting started. Start with the least scary thing you can think of, and work your way up. With each step, it’s good to think about what your child would predict, and after following the step, was the prediction fulfilled? Giving lots of praise and a non-monetary reward (time with you, doing something fun) may help the process.

Myth Four: My child will grow out of it

Fact: Children do not just grow out of anxiety

Anxiety problems are the most common problems in childhood. Children often do not grow out of their anxiety. In fact, anxiety is often a risk factor for depression in adolescence and adulthood. Therefore, it is essential that they receive help understanding and managing anxiety.

Myth Five: Anxious children are shy

Fact: Shyness and social anxiety are not the same

A child or teenager dealing with anxiety, such as social anxiety, is full of self-doubt and uncertainty, making them unable to speak to others in certain situations. This is different to shyness.

Some of the most common fears found in children with social anxiety (often begins to show itself more during the teenage transition) include fears about performance situations, such as speaking or performing in front of people (e.g. musical recitals, plays, etc), and social interactional fears, such as joining or starting a conversation and interacting with peers.

Sometimes it is more generalised, so they:

- Find it difficult to start conversations with unknown children or adults

- Seem uncomfortable in groups and refuse to join in

Other times, it is focused on one specific fear and how they seem to others; they may:

- Avoid speaking in front of the class or other performance-related issues due to blushing

- Feel people are looking at them when they are eating.

These children would like to socialise and converse with others, but their anxiousness prevents them from doing so. This is not simply shyness, but rather a symptom of anxiety.

Myth Six: As a Parent, I cannot help my child

Fact: Evidence shows Parent Power works

I receive many referrals from parents to work with the child independently, which is fine. However, I am also interested in empowering parents. I believe parents have an in-depth understanding of their children, far surpassing anyone else. Their responses to situations can be the fork in the road, leading either to a positive or negative outcome. It can either help a child see that there is a way out, that things aren’t as scary as their anxious thoughts are making them feel. On the other hand, responding with your own fears to your child’s behaviour can inadvertently reinforce fears by lending credibility to them. The more you learn about how anxiety works, the more you can integrate that information into what you already understand about your child. This will empower you to feel competent and help your child feel secure.

There is evidence that also backs this up. (C. Jewell, A. Wittkowski, D. Pratt 2022; The impact of parent-only interventions on child anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis) that shows parents can empower their children. I am passionate about empowering parents, and I am running a parent workshop on anxiety in November. Please join my newsletter to be informed or contact me via my contact form.

Myth Seven: My child may never be cured

Fact: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy has been proven effective in helping reduce anxiety.

Many mums and dads worry their kids may not make a full recovery. Nevertheless, the study indicates that cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) helps kids handle their fears and can lead to healthy adulthood. Additionally, going through the phases of enduring and tackling troubles can teach a valuable lesson in resilience.

Developing resilience in our children can help them adapt well to any adversity, tragedy, danger, or stress they may face. Even if they face hardships, it doesn’t mean they won’t feel difficult emotions, such as sadness or anxiety. It is normal to feel such emotions when dealing with trauma or loss, whether it be your own or someone else’s.

Seek help if:

- The intensity of the fear or worry is so high it starts to impact your child’s functioning and well-being.

- It impacts family life, school and social activities

- The anxiety and level of worry are out of context with their developmental stage and age.

In Conclusion

It is an unavoidable fact that stress and nervousness are part of daily living. Nevertheless, when anxiousness becomes overwhelming, it can disrupt both yours and your offspring’s wellbeing and life. Do contact me if you feel you need some help. With Love Catherine

Further Posts: