The pandemic has had a massive impact on everyone, but especially children. Parents and professionals like myself have noticed an increase in anxiety, although the long-term effects and extent of the problem remain. Recent events make talking to your children about anxiety even more critical.

Many parents often feel concerned that talking to their children about anxiety will make them even more anxious. However, they may think something is wrong with them if you don’t. I have seen young people who thought of themselves as unusual and inadequate, leading to feelings of dejection and hopelessness. Therefore, it is vital that you help your children understand that it is not them but anxiety.

Here are three steps to talking to your child about anxiety, the research, and examples of anxiety disorders.

The Research on Anxiety

Anxiety is the most common mental health condition in children. Hence, it doesn’t distinguish between age, background, or social group. In 2017, 3.9% of 5-10-year-old children had an anxiety disorder, as did 7.5% of 11-16-year-olds and 13.1% of 17-19-year-olds (Ref. https://mhfaengland.org).

We are already seeing that the stress of the pandemic has a tremendous impact on young people’s mental health (aged 16 to 24). Stress and uncertainty around education, employment prospects, and reduced peer social support have increased depression and anxiety. ( The MQMental Health Research).

Three steps to talking about Anxiety

- Start by describing a recent situation when you observed your child is anxious. ( Children are often nervous at new social problems and transition times, often when they have to leave you)

When we went to Jenny’s house, I noticed you seemed very quiet and need to stay with me for quite a long time. I wondered if you were a bit nervous about being in a new house.

- Please help them identify their fears; you may have to offer a prompt.

I know some children are scared of the dark and have fears at nighttime……do you have that worry too?

- Share your fears and worries that you may have had as a child and ask if they have the same.

- Accept your child’s fears, tell them you believe in them, and empathise with how hard that is for them.

What not to say to Anxiety

Secondly, talking and teaching your child about Anxiety

- Ensure your child has an emotional vocabulary. Do they have a word for anxiety, such as fear, worry, or being scared?

- Communicate that anxiety is normal, and everyone feels stress or worries sometimes. So, it is customary to fear being away from mummy or daddy. It is normal to feel worried before a test or competition.

- Anxiety is not dangerous within itself. However, it is uncomfortable, but the feeling/s will pass.

She was talking and explaining the Fight-Flight-Freeze ( stress response).

Children like a bit of simple science, which helps them to understand the relationship between the Amygdala and Hippocampus for the stress response:

The Role of the Amygdala

Did you know that this response goes back to cavemen times? It’s the part of the brain called the Amygdala. This is online from birth. It’s like a susceptible guard dog that barks and helps us decide what a threat is. It uses sight, sense, and smell. (It does not use thought; it is mindless). It makes this decision fast (a tenth of a second) whether it needs to save your life. It will decide whether to:

- Fight ( lash out at others)

- Flight ( run away or avoid situations)

- Freeze ( mind, body go blank or freeze)

It often triggers “false alarms” and potentially problematic reactive behaviour. We sometimes freeze in stressful situations, like public speaking or taking a test.

The Role of the Hippocampus

The Amygdala works together with the part of our brain called the hippocampus. This is like a security guard ( or librarian). The guard’s primary duty is to note different facts, such as the time, location, and what happened at various stages of an event. This process is like putting a tag on your memory. It is much slower and more thoughtful, helping you construct memories.

For ordinary events in daily life, the guard dog (Amygdala) and the security guard (Hippocampus) have a pretty good relationship. They work together and cooperate reasonably. For example, when the dog senses a potential danger, it will bark to get your attention, and the guard will check it out. After checking the records of your previous experiences and life events, the guard will decide if this situation is a real danger or a false alarm. If it’s a real danger, they will agree with the dog to continue with the ‘fight or flight behaviour to save your life. If not, they’ll reassure the dog, which stops barking. After a short while, they return to their normal state and leave your brain and body relaxed.

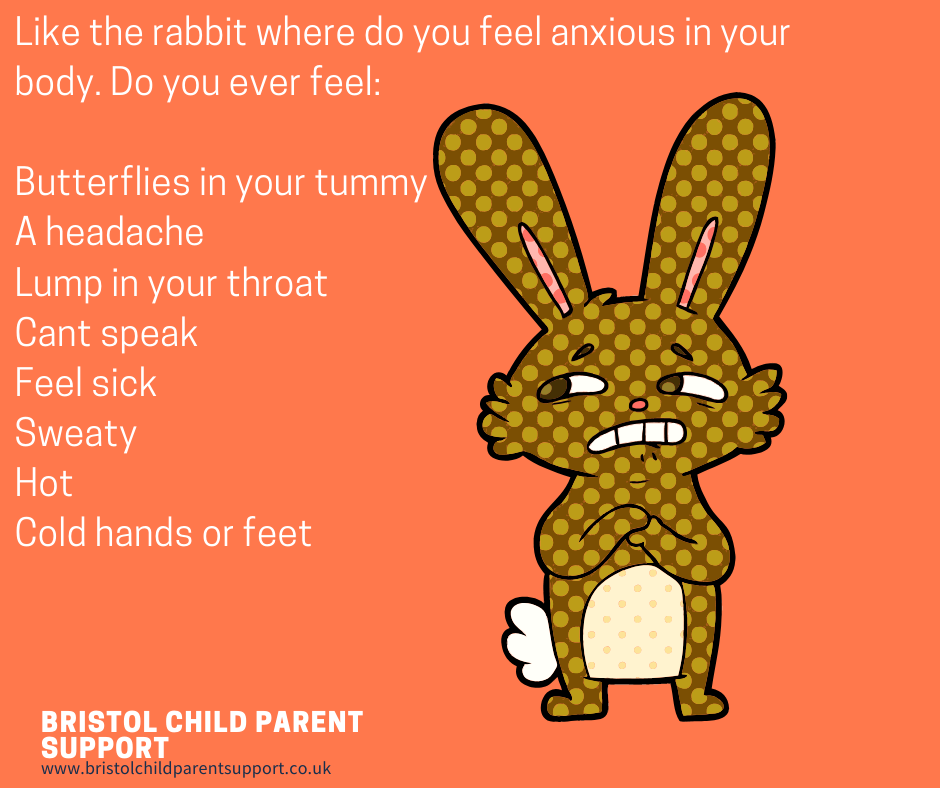

Lastly, how to help your child recognise Anxiety.

Anxiety affects our thoughts, body responses ( physical feelings), and actions ( behaviour ). It sends signals from the brain to our bodies, muscles, and hormones. This is why you may be feeling sensations such as:

Anxiety Symptoms, You may notice your child suffering from Physical Symptoms such as:

Sit down with your child and help them identify physical symptoms; they may soil, be constipated or suffer from daytime and nocturnal enuresis. Younger children are much more likely to locate anxiety as a physical symptom.

- Lots of tummy aches

- Feeling sick

- Headaches

- Feeling dizzy

- Dry mouth

- Wanting to go to the toilet a lot

- Soiling/Bedwetting

- Not being hungry or wanting to eat too much

If it is age-appropriate, give the anxiety a name such as:

- The worry monster

- The scariness

- Mr worry

- The wibble wobble

Please help them understand how anxiety or worry affects their thoughts.

Children often suffer from negative thoughts. As a result, they may:

- Worry about family’s health and preoccupied with death

- Suffer from many” what if” thoughts; they often seem unrealistic and occur in the future.

- Feel they are “getting it wrong “; hence, children “ruminate” over and over on something that occurred during the day at school (e.g. they may have got something wrong in a lesson)

- Think the worst, “catastrophising” about what may occur.

Therefore, it’s good to ask children to identify their thoughts and take back control by “bossing” Mr Worry.

For older children, use the music analogy, “it’s as if the volume is turned up and the anxiety is loud”! These strategies help your child adopt a sense of control and detachment from stress and fears.

Help them be a detective of their thoughts. Examples are:

How Anxiety affects your child’s behaviour

Behavioural Symptoms of Anxiety

- Marked avoidance of certain situations that they used to ( people, school, places, and animals) and may start to impact their day-to-day life.

- In younger children, you may notice extreme aggression or meltdowns directed or distress and extreme crying before a situation.

- I do not want to go to bed or sleep alone—nighttime fears, waking in the night, and many nightmares.

- Safety behaviours, children develop routines that they need to do to feel safe and keep their anxiety at bay. Other safety behaviours seek constant reassurance from you. Please note that safety behaviours offer temporary relief and sometimes maintain anxiety.

- Find it hard to separate from you and want to cling to you.

- Some children do not speak in certain situations, which is “selective mutism.”

- Some children develop fears around illness; they think they are ill, but are anxious.

Note: Prolonged anxiety can lead to low mood and depression.

Please note safety behaviours only give temporary relief and sometimes maintain the Anxiety.

What types of Anxiety are there?

Generalised Anxiety ( GAD)

Sometimes, we suffer from worries and anxiety. However, children who present with generalised anxiety have many fears, thoughts, and feelings. They may want to avoid certain situations; this can be hard for you to understand. You may feel unrealistic and become annoyed with anxiety, but their worries interfere with your daily life. Seek support when your child has been showing signs of stress for more than a few weeks. If their mood has lowered, your child is distressed, schoolwork has suffered, and they are not socialising or enjoying activities as they did before.

Separation Anxiety

Separation anxiety is a normal developmental stage. During these ages, it is normal to have fears of separating from your parents or carers, and children are dependent on their carers, so it’s natural they will feel vulnerable when they are apart. Most children grow out of it; some do not grow out of it; these children may have difficulty saying goodbye, have lots of tummy aches or headaches and cling at times of separation. As a result, the distress often prevents them from participating in age-appropriate activities and learning opportunities like joining sports teams or attending school.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD )

OCD is a severe persuasive disorder where your child experiences frequent obsessive and intrusive thoughts (or obsessions), often followed by uncontrollable urges and compulsions. For more information, go to my Blog.

Phobias and Fears

A phobia is a persistent, excessive and unreasonable fear of an object or situation. 5% of children and 16% of teenagers have a phobia in the UK. Phobias are different from usual fears as they become more severe with age. Children and teenagers with a phobia often feel huge shame about their fears, often because messages from others may be that they are being silly or overreacting.

Social Anxiety

We all might worry about what other people think of us and become anxious. Children with Social Anxiety avoid attending clubs, eating in front of others and many other social events. This might mean they become socially withdrawn and may even develop school refusal. For more on Social Anxiety versus shyness, read more at my Blog.

Panic Attacks and Disorder

A specific event can trigger panic attacks, such as in a crowded room, or come on without explanation. The unpredictability of panic attacks can make them even more terrifying. If your child has had multiple panic attacks, they become more fearful and want to avoid future situations. They are much more intense than feeling anxious; your child may feel.

- As if they are dying

- They are trembling

- Sweat

- They are unable to breathe

- Shake uncontrollably

- Dizziness

- Racing heartbeat

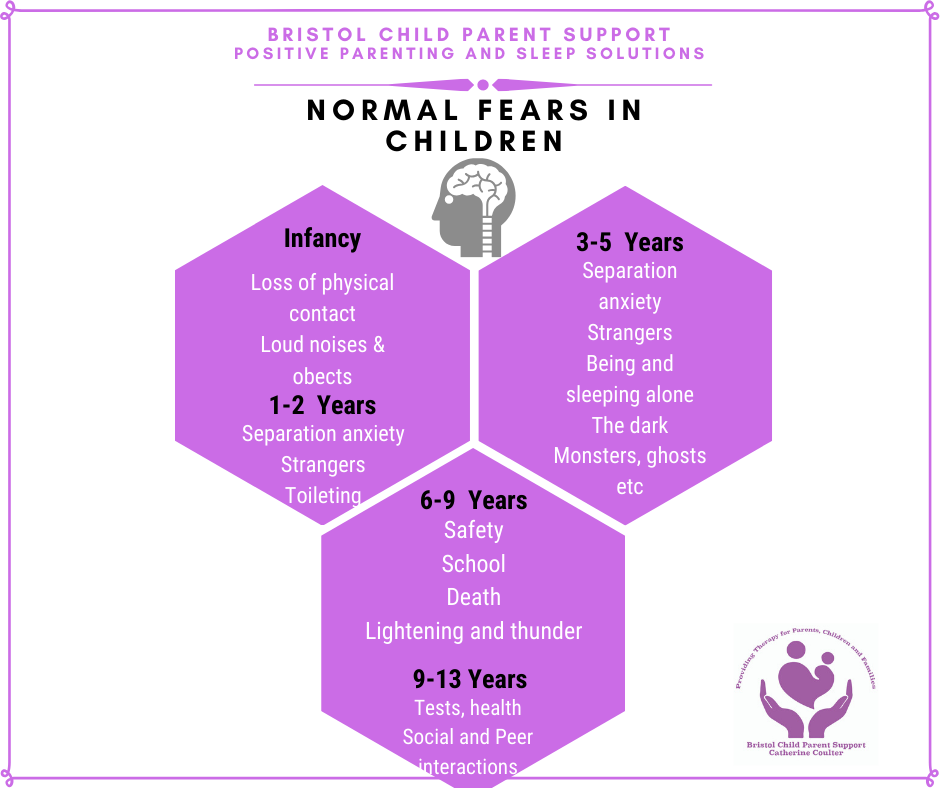

Recognising Normal Fears versus Anxiety Disorder

Fears and worries are a regular part of your child’s development. Most children can report several fears at any given age. If the fear isn’t affecting their life (like sleep or school performance) or the family, you don’t need to take your child to a health professional. But if it is, contact a health professional.

Anxiety disorders occur when:

- The intensity of the fear or worry is so high it starts to impact your child’s functioning and well-being.

- It impacts family life.

- The anxiety and level of worry are out of context with their developmental stage and age.

In Conclusion

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Thank you for being so committed to your child’s well-being and family. Remember: parenting is hard work, and you deserve support. Do contact me if you feel you need some help. With Love Catherine