As parents, it is natural to worry about our children’s well-being, especially when it comes to their mental health. Anxiety is a common emotion experienced by everyone, including children. However, it is important to distinguish between normal anxiety and an anxiety disorder. In this blog post, I will explain the six types of anxiety disorders that may affect your child and additionally the causes of anxiety. This is the second in a series of articles about anxiety.

Why do we need to care about children’s anxiety?

Anxiety disorders are one of the most common disorders. According to NHS England.

One in five children and young people in England aged eight to 25 had a probable mental disorder in 2023, a new survey shows. Despite being aware of it, anxiety disorders continue to remain undetected.

The Mental Health of Children and Young People in England 2023 report, published by NHS England, found that 20.3% of eight-to 16-year-olds had a probable mental disorder in 2023.

Among 17 to 19-year-olds, the proportion was 23.3%, while in 20 to 25-year-olds it was 21.7%.

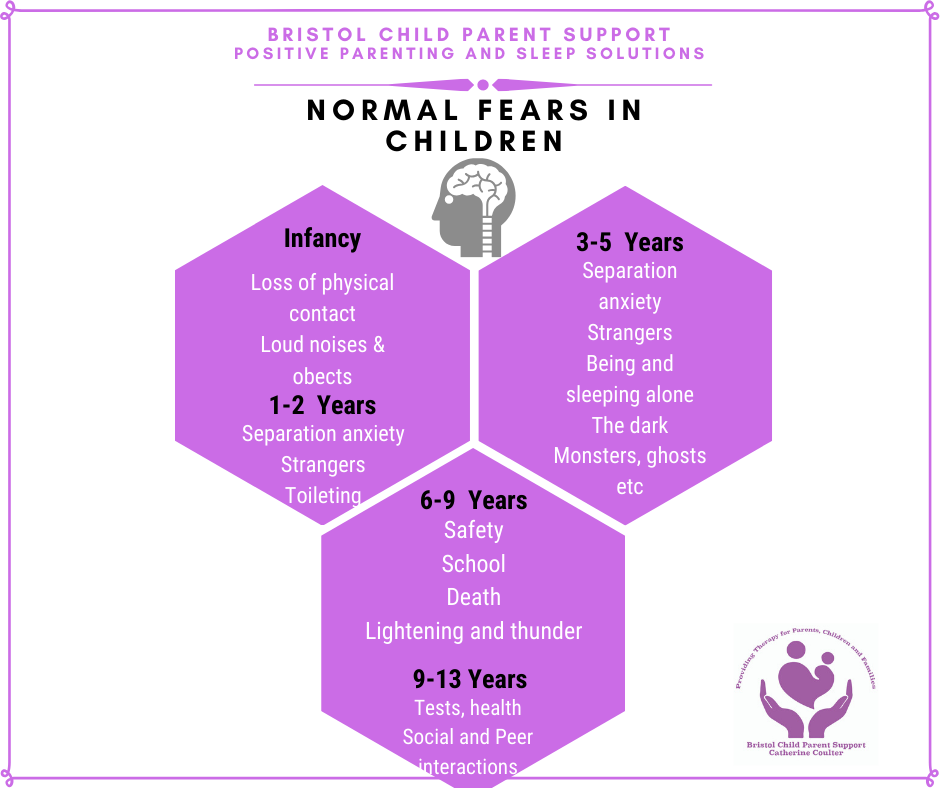

Normal Anxiety

Children often experience anxiety in various situations, such as starting school, taking tests, or making new friends. This type of anxiety is usually short-lived and does not significantly interfere with their daily lives. It is a natural response to new experiences and can even help them develop resilience and coping skills.

What is the difference between fear and anxiety?

The definition provided by the American Psychiatric Association, in my opinion, aids in identifying a typical response to fear and how it can escalate into anxiety.

“Fear is the emotional response to real or perceived imminent threat, whereas anxiety is anticipation of future threat. Obviously, these two states overlap, but they also differ, with fear more often associated with surges of autonomic arousal necessary for fight or flight, thoughts of immediate danger, and escape behaviours, and anxiety more often associated with muscle tension and vigilance in preparation for future danger and cautious or avoidant behaviours”. ( APA 2013).

Anxiety Symptoms in Children: What Signs to Look out For:

Physical Symptoms

Physical symptoms are very real for children and teenagers. You will probably know that they are caused by the flight or fight or freeze stress response.

This is a primitive defence mechanism which evolved to enable us to react when faced with danger. To run away, to fight, or sometimes freeze in order to keep ourselves safe.

When our fight or flight response is activated, our body undergoes various physical changes. These changes include muscle tension, increased heart rate for better oxygen circulation, and a temporary halt in digestion. This redirects blood to the arms and legs, which can cause feelings of sickness or “butterflies” in the stomach.

This may also be why your child complains of:

- Lots of tummy aches

- Feeling sick

- Headaches

- Feeling dizzy

- Dry mouth

- Wanting to go to the toilet a lot

- Not being let go into sleep and sleep difficulties

- Not being hungry or wanting to eat too much

Signs of excessive worry

One of the primary signs of anxiety in children is excessive worry. They may constantly express concerns about everyday activities, school, friendships, or even future events. These can occur at nighttime when there are less distractions and additionally it is a time of transition, going from one state into another. Overall , the worry may be disproportionate to the situation and can interfere with their daily functioning.

Emotional outbursts

Many parents are surprised when I tell them that their child, who appears angry, may be struggling with anxiety. Anxiety can lead to emotional outbursts in children. They may experience sudden bursts of irritablity, anger, tears, or meltdowns that seem out of proportion to the situation. These emotional reactions are often a result of their struggle to manage their anxiety. This is particularly noticeable when children experience daytime anxiety in school and then usually come home and exhibit explosive behaviour..

Signs of changes in behaviour

Children may display changes in their behaviour due to anxiety, such as increased irritability, frustration, or trouble focusing. They may also show signs of clinginess, separation anxiety, or a need for constant reassurance from their caregivers or parents.

Avoidance behaviour

Children with anxiety may exhibit avoidance behaviour, trying to avoid situations or activities that trigger their anxiety. This could include avoiding social interactions, school events, or even specific places or objects. When your child becomes socially isolated, it can negatively affect their self-confidence and ability to interact with others. By not engaging with others, they miss out on opportunities to improve their social skills. This may even result in social anxiety disorder, or excessive fear and discomfort in social situations. In severe cases, a child may develop selective mutism, where they are too afraid to speak in specific environments. Be mindful of any avoidance behaviours and approach them with compassion and consideration.

Agitation and inability to concentrate

If a child is in a situation where they don’t feel safe, their body is primed to detect danger rather than for learning. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for rational thinking and planning, will not function efficiently. In survival mode, this part of the brain takes a back seat to the more primitive responses located in the amygdala and limbic system. The child’s body prepares to fight or flee, rather than sit calmly, and learn. This can result in restlessness, difficulty concentrating, and being easily distracted. Younger children may appear constantly on the go, all over the place, wired and unable to focus on one task. Older children may also display these behaviours, or seem “ zoned out” and detached. My article on, What if not all Attention Difficulties may be ADHD, includes more details on how restlessness and lack of focus can be misconstrued as ADHD.

Wanting to control

Sometimes, children try to control certain areas of their lives. They may restrict their eating or become very strict about when and what they will eat. They may also become more rigid in their thinking and refuse to compromise. This can make it hard for the family, as they may feel like they always have to bend to the child’s will. Often, when the world feels scary and unpredictable, children try to control what they can. They do this because they are feeling anxious and are trying their best to manage these feelings. Control always feels better in the short term, but in the longer term, by giving in to your child, you may inadvertently be maintaining their anxiety.

Some general tips to support your child

- Create a Safe and Open Environment: Foster a safe and non-judgmental space where your child feels comfortable expressing their emotions. Let them know that it’s okay to feel scared or anxious and that you are there to support them.

- Validate Their Feelings: Acknowledge and validate your child’s emotions. Let them know that their feelings are valid and that it’s normal to feel scared or anxious at times. This validation helps them feel understood and accepted.

- Use Age-Appropriate Language: Tailor your language to your child’s age and developmental level. Use simple and concrete terms to explain emotions and fears. For younger children, you can use visual aids or storytelling to help them understand.

- Encourage Emotional Expression: The biggest thing you can do is just talk about emotions,” Taking opportunities to talk about and label your own emotions or the emotions expressed in a children’s TV show or book can be helpful. It is also helpful for parents to label emotions that a child is expressing for them so that “in the future, they can then learn to label it themselves. Encourage your child to express their emotions through words, drawings, or play. This allows them to externalise their fears and gain a sense of control over their emotions.

- Label Emotions: Help your child identify and label their emotions. Use words like “scared,” “anxious,” or “worried” to describe what they are feeling. This helps them develop emotional awareness and build their emotional vocabulary.

- Connect Emotions to Behaviours: Help your child understand the connection between their emotions and their behaviours. For example, you can say, “I noticed that you get really quiet and fidgety when you feel scared.

- Model Emotional Regulation: Be a role model for your child by demonstrating healthy ways to cope with and regulate emotions. Show them how to take deep breaths; practise deep belly breathing.

Remember, the goal is not to eliminate all fears or anxieties but to help your child develop healthy coping mechanisms and emotional resilience. By using affect labelling and providing a supportive environment, you can empower your child to navigate their emotions and fears in a positive and constructive way.

When to be worried and seek help.

As a parent, it is beneficial to consider the three D’s when evaluating the need for assistance. If your child’s anxiety is affecting their daily life, it may be necessary for them to seek help from a licensed therapist like myself. Contact me for a consultation

The first line of treatment is usually talking therapy. Alternatively, speak to your healthcare provider or family doctor in the first instance. Your child’s school may also be able to make a referral.

What are the six types of Anxiety Disorder

Anxiety disorders are common in children and young people are common and can have a significant impact on mental health and well-being. Anxiety disorders can affect family, school, and social life, leisure activities, and educational achievement, and they often occur alongside other mental health problems. Your child is more likely to suffer from anxiety if they have autistic spectrum disorder and ADHD. Sometimes, Anxiety can occur independently of ADHD. Other times, it can be a result of living with ADHD. Children with ADHD often have more trouble managing stress than children who don’t have ADHD. That’s because ADHD affects how children manage their emotions.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders lists six types anxiety disorders

Separation Anxiety

Separation anxiety is a natural developmental stage. The baby may weep if its mother is out of view for a short while, while the young child may hold onto you or throw a tantrum when they are about to start school for the first time. Since children depend on their carers, it’s natural for them to feel vulnerable when you leave them. Although the degree and duration of separation anxiety may differ greatly among children, it is crucial to keep in mind that feeling a little anxious about being away from parents is normal, even as a child grows older.

However, some children experience separation anxiety that doesn’t go away, even with a parent’s best efforts. These children experience a continuation or recurrence of intense separation anxiety during their junior school years or beyond. They often complain of tummy aches, headaches, or other physical symptoms. The distress prevents them from participating in age-appropriate activities and learning opportunities like joining sports teams or, in some cases attending school. The anxiety often means that they need their parents to be constantly present. Therefore, this is often time-consuming and tiring for parents. I also need to point out that it is not just young children that suffer from separation anxiety. Teenagers can too. You may also notice:

- Clinging to parents

- Repeated nightmares with a theme of separation.

- Worry or panic when faced with separation from home or family.

- Withdrawing from social situations with friends and hobbies

- School refusal and poor school performance.

- Extreme fear or reluctance of being alone, sometimes at bedtime.

Generalised Anxiety ( GAD)

Children with GAD can worry about just about everything and anything, and the worry is often chronic, long-lasting, and hard to control. The difference between normal feelings of anxiety and the presence of a generalised anxiety disorder is that children with GAD worry more often and more intensely than other children in the same circumstances. Another distinguishing factor in GAD is that anxiety focuses not on external triggers like social interaction or contamination but internally. Children with GAD tend to seek frequent reassurance from caregivers, teachers, and peers about their performance, although this reassurance only provides a fleeting relief from their worries. Not only will you notice physical symptoms, but you may notice lots of questioning and your child trying to manage the outcome of their future,

Anxiety always anticipates the future, and your child may use many “what if questions”.?

Will we get there on time?

What if I can’t fall asleep the night before the test?

You may also notice negative thinking patterns,” cognitive distortions”. Sometimes they can be referred to as challenging thoughts and even thinking mistakes or errors. They are often unrealistic but, above all and are overly self-critical. Unlike adults, children cannot realise their beliefs are outsized and unrealistic.

Panic disorder

This often starts in older children and young adults. It’s the repeated fear of impending doom or danger which develops after unprovoked physical symptoms, such as rapid heart rate, shortness of breath, dizziness, and choking sensations, and sweating.

Specific phobia

This is an extreme or unreasonable feeling of fear or anxiety linked to a specific animal, object, activity, or situation. This fear causes extreme distress and can stop children taking part in normal day-to-day activities (Evans 2012). I’ve worked with parents and children with fear of insects ( flies and bees), rain and dentists.

Social Phobia

This refers to persistent anxiety in children or young individuals when faced with social or performance scenarios involving unfamiliar people, where they feel like they are being closely observed (APA 2013).

They may also avoid situations that trigger this fear. The child may worry about behaving in a way that is shameful or humiliating, which can result in a panic attack (APA 2013). They may either avoid these distressing situations altogether or participate in them with extreme unease and discomfort (APA 2013).

According to the Nice Guidance, there are several specific symptoms (one or more) that can indicate a disorder in your child if they have been present for a prolonged period.

- They might worry about doing things with other people watching. They might get scared that they will do something silly or that people will make fun of them. Therfore, school can be a big trigger them.

- They might not want to do these things, or, if they have to do them, they might get very upset or cross.

- Does your child get scared about doing things with other people, like talking, eating, going to parties, or other things at school or with friends?”

- Does your child find it difficult to do things when other people are watching, like playing sport, being in plays or concerts, asking, or answering questions, reading aloud, or giving talks in class?”

- Does your child can’t do these things or try to get out of them?”

Selective mutism

This is when a child consistently fails to speak in situations in which they are expected to speak, such as at school (APA 2013). Selective mutism isn’t a communication disorder and it’s also not the child being uncomfortable with speaking in those situations, or not knowing what to say (APA 2013).

Children who have selective mutism can communicate confidently and successfully in environments where they feel at ease, safe, and relaxed. They may speak at home with their immediate family or with their closest friends.

Why is it that children experience various types of Anxiety Disorder?

The Association of Child and Adolescent Mental Health acknowledges the causes of anxiety disorders is complex. Genetics, family dynamics, and environmental factors are believed to contribute to their development. Risk factors include:

- Genetics – anxiety disorders tend to run in families.Children of parents with an anxiety disorder are seven times more likely to have an anxiety disorder, compared to children of parents with no disorder.

- A child’s temperament – for example, an inhibited, sensitive temperament in early childhood is a risk factor for anxiety disorders in middle childhood and mid-adolescence. Information processing biases may also be a factor- for example if a child interprets ambiguous situations as threatening.

- Emotional neglect in childhood, such as rejection, criticism and a negative relationship with their main attachment figure (usually a parent).

- Stressful life events and Trauma

Unfortunately, as parents, we do have an impact on our children’s capacity to manage anxiety. Surprisingly, if we are over-involved in our children’s lives, it can lead to anxiety as well as parent-parent conflict.

How would you know when your child’s anxiety becomes a disorder?

Remember the three D’s, distress, duration and disruption, you can check this out in my last article

Anxiety disorders are characterised by excessive fear, anxiety, and worry about events or activities, and this happens more often than not for a child and continues for at least six months (American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V). The anxiety or worry, or physical symptoms that arise as a result, can cause significant distress to a child or young person and affect their quality of life and ability to function day-to-day.

Treatment for Anxiety Disorders

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the primary approach for treating anxiety disorders in children and adolescents, and has proven to be successful. This therapy can be administered in different formats, such as parent-guided sessions, computer-based programs, and in-person meetings. While medication may also be an option, it is not commonly recommended.

CBT is not suitable support for everyone

One of the main reasons CBT may not be suitable for every child is their age. Young children, particularly those under the age of 8, may not have the cognitive ability to fully understand and engage in CBT techniques. CBT relies heavily on cognitive skills such as introspection, self-reflection, and problem-solving, which may be beyond the developmental level of young children. In these cases, age-appropriate therapeutic approaches, such as sandplay/play therapy or art therapy, may be more effective.

Another consideration is neurodiversity. Neurodiversity refers to the natural variations in brain function and behaviour that exist in the population. Children with neurodiversity, such as those with autism spectrum disorder or ADHD, may have challenges with learning and processing information in the same way as neurotypical children. This can make it difficult for them to fully engage in and benefit from traditional CBT techniques.

In Conclusion

Understanding the difference between normal anxiety and an anxiety disorder is crucial for parents. While occasional anxiety is a part of life, an anxiety disorder can significantly impact your child’s well-being. There is evidence that most young people with anxiety disorders don’t access clinical services, and therefore don’t receive treatment, which can often lead to academic and social difficulties that go into adulthood. By recognising the symptoms and seeking professional help, your GP or school nurse and school when needed. Contact me for a consultation, or workshop if you want to help children now.

Let’s act and stop the worry cycle now. With Gratitude Catherine

.