Did you know that children are not born with the capacity for self-control? Helping your child regulate is one of the most critical tasks in parenting and within ourselves. Emotional regulation and executive functioning skills are interlinked, and I hope this blog will explain this further.

What is Self/ Emotional Regulation?

Self-regulation is the capacity to manage emotions and behaviour following the demands of the situation. We can also calm/self-soothe when upset and be flexible to change an expectation or routine. Your child can stay focused on their goal despite internal and external changes.

The development of self-control/regulation takes time. If you are parenting a toddler, tantrums and “big feelings” are all part of this process.

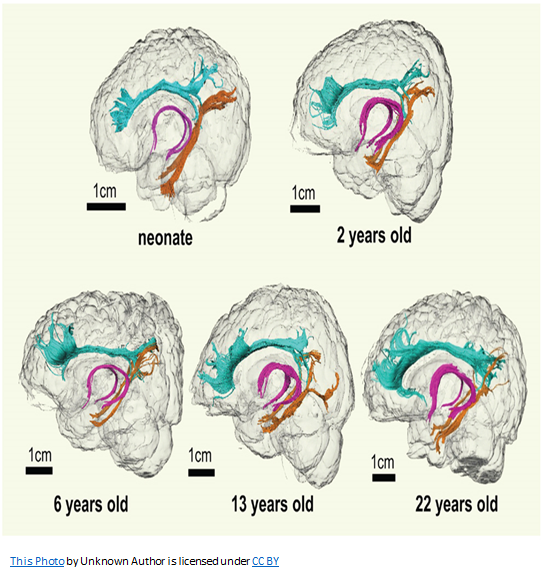

Self-regulation and executive functioning skills develop over the years (some say that the brain is fully adult at 24). Mainly the most significant changes occur between 3-7 years and adolescence. The brain “rewires itself” during adolescence, especially in the prefrontal cortex areas. This is the last region of the brain to mature.

Why is Emotional Regulation so complex in Children?

When babies are born, their brains are not yet well developed. We can think of their brains developing as building a house. ( downstairs and upstairs). They are learning to create the upstairs brain and, in particular, specific skills called executive functioning skills. They are housed in the prefrontal cortex. Often emotional regulation and executive functioning skills are seen as separate entities. The image below demonstrates the development of the cortex (the blue colour):

There is further information in this workshop I ran in Lockdown.

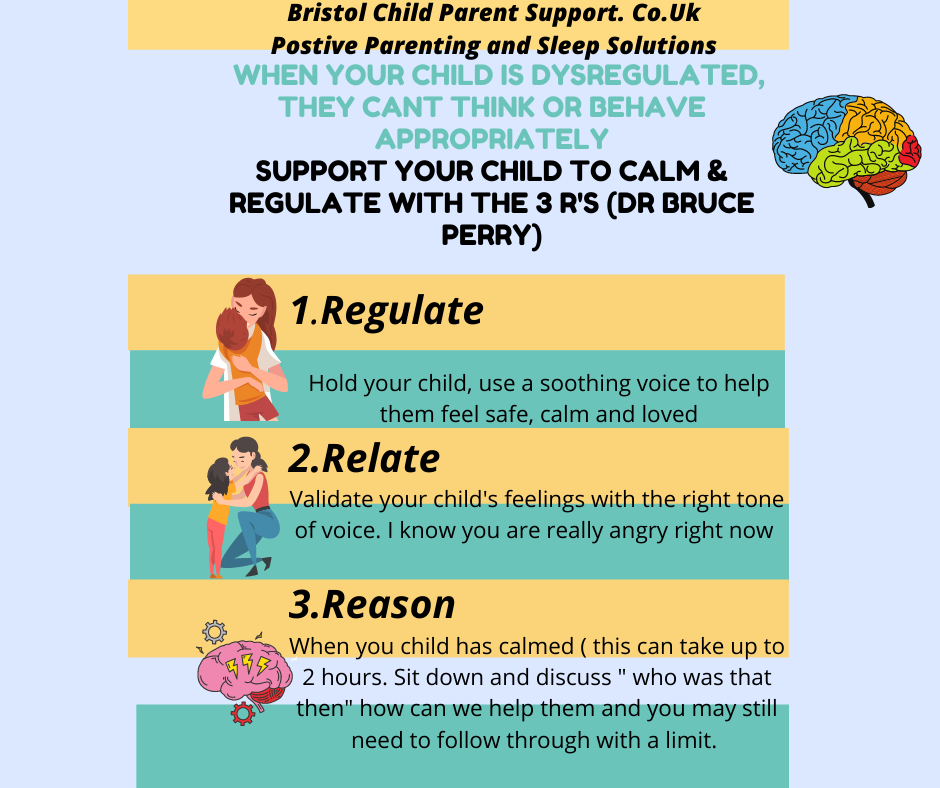

However, our ability to think clearly and put the executive function into action directly relates to what we feel and how intensely we feel. If we become dysregulated in our emotions, it will impair our administrative function skills. When stressed or upset, the prefrontal cortex shuts down and no longer works with the rest of the brain. We subsequently lose the capacity to problem-solve. It is pointless to reason with your child, wait, and discuss it later during these times. Keep in mind Dr Bruce Perry’s 3 Rs.

There are three main areas of executive function. They are:

- Working memory

- Cognitive flexibility (also called flexible thinking)

- Inhibitory control (which includes self-control)

These can be broken down further into six domains.

(Ref: Attachment, Developmental Trauma, and Executive Functioning Difficulties in the School Setting. Marion Allen. Family Futures).

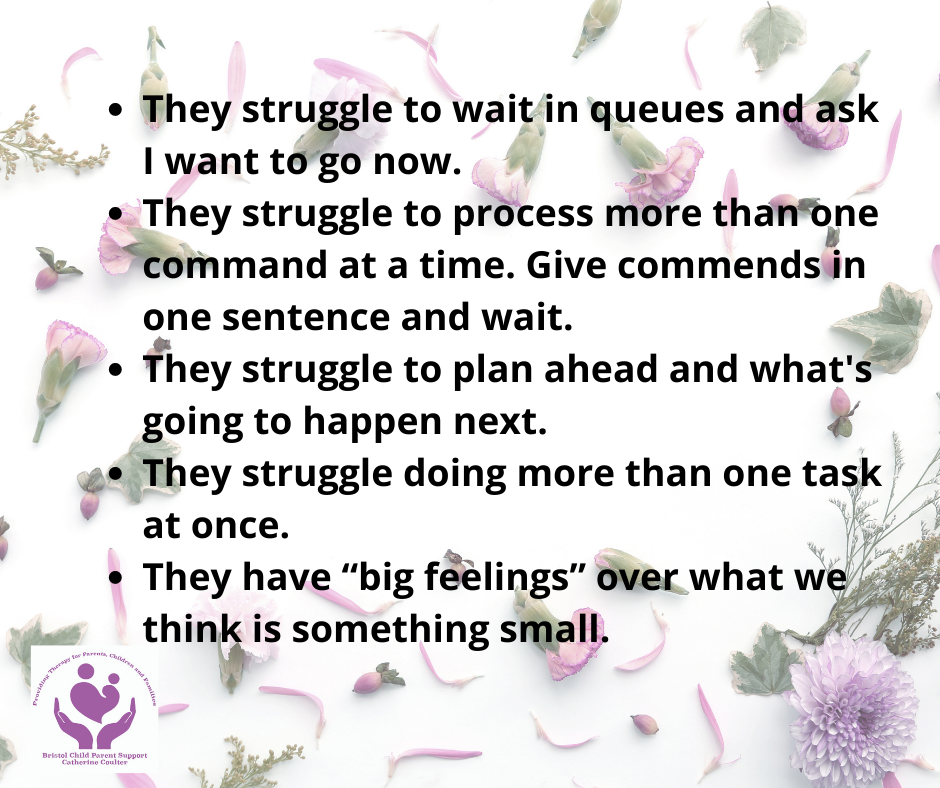

- Inhibit– the ability to stop one’s behaviour at appropriate times. It is our “edit” button. This is the capacity to take a pause. These children shout out in class and have difficulties in unstructured times at school. This is often “one” of the characteristics of ADHD.

- Shift/sequencing-Move from one thing to another and for it to be smooth. I see many children who struggle with transitions and present as disorientated by a change of routine. This is often evident at night and going out to school or nursery.

- Emotional Control-. How to regulate emotions. Even though ALL children are learning in this capacity) some children struggle more. Their internal emotional state can frequently shift, resulting in angry, distressed, or over-excitable behaviour.

- Working Memory-It’s the ability to hold on to new information to complete a task. Working memory allows us to hold information without losing track of what we’re doing—for example, cooking and following a recipe.

- Plan and organise– This relates to the ability to implement, plan, set, and work through the steps to achieve the goal. Many teenagers struggle to start a task or what they might need to bring to class.

- Self Reflection/monitor– This is the ability to look and notice behaviour as others do and its effect on another person. This also includes checking and monitoring work. Many children I’ve worked with struggle with why their work wasn’t given a good mark, and often see life through the lens of being unjust and unfairly treated.

Normal Emotional Development.

This is always a difficult question. Each child’s brain develops at different rates. A three-year-old is going to have less capacity to manage than a 7-year-old. All children present with emotional dysregulation at times, which is perfectly normal. It would help if you considered whether it is developmentally appropriate. Here is a guideline:

- 5-12 months- the start of behavioural inhibition and working memory (nonverbal).

- 5-12 months- self-regulation of affect and arousal.

- 3-5 years- verbal memory. It is then not internalised until 9-12 years.

- Six upwards-cognitive, behavioural flexibility and creativity.

(Ref: Attachment, Developmental Trauma, and Executive Functioning Difficulties in the School Setting. Marion Allen. Family Futures p4).

You might notice:

- Adolescence-24 years of age.

If you are parenting an adolescent right now, you will notice the impact of the changes in their brain. Often this begins just before (the pre-pubescent stage). Teenagers are heavily dependent on their emotional Limbic systems. Thus, interpersonal interactions and decision-making are more impulsive. This partially explains why they are quick to anger, have intense mood swings, risk take more, sensation seeks, and make decisions on “gut instinct” rather than a logical reading of the situation. It can be baffling to be a parent at this time. On the next occasion your teenager “blows”, try not to take it personally; it’s a “brain thing”; however, being accountable is essential too.

How can I help my child?

- The brain adapts to its experiences. We know positive interactions in the early years impact how we learn, regulate emotions, and develop trust in relationships.

- Emotionally responsive parenting helps your child to cope with stress. The way you talk to your child makes a difference! Necessary action is not just to talk to your child but to talk with your child. It’s not just about dumping language into your child’s brain but carrying on a conversation with them. A study showed parents should perhaps talk less and listen more.

- Be developmentally appropriate with expectations.

- Make a simple weekly planner, which is especially helpful for children suffering from anxiety and younger children with developing working memory.

- Give instructions and commands one at a time.

- Avoid helicopter parenting; teach your child to problem-solve. For example:

- What do you need to do to complete your schoolwork?

- Oops, how do you think you could clear that up?

- Two choices, which one?

- How can you and your sister solve that problem?

- What do you need to put on if you don’t want to be cold outside?

- Use visual charts to explain expectations and sequencing. For example, the one below for the morning routine.

- For older children, post-it reminder notes help.

- Take a pause; self-regulation and executive functions come in limited quantities. They can be depleted quickly when your child works too hard over a short time (like while taking a test). Give your child a chance to refuel by encouraging frequent breaks during tasks that stress the executive system. Breaks work best for up to 10 minutes.

Lastly, whatever your child’s age, offer them individual play as a “special time”. Playing with your child provides so many benefits.

In Conclusion

None of us thought we would be parenting at such a challenging time. Hence, It’s more important than ever to let go of the fallacy of being the perfect parent; good enough is just fine!

When something goes wrong, try to see their need and what might be behind the behaviour, rather than blame your child or yourself. Stay with any immense feelings (yours and theirs) and then validate their emotions. Sometimes we all need to pause, regulate, and then return to talking when everyone has calmed.

If you want to transform your connection with your child in 2023 or start to have a good night’s sleep, Contact me for a Consultation. with love, Catherine.

Please share this with anyone who may find it helpful.